Riding the Majic BusThe DebeVoiceby Townsend Davis   |

In April [1998], I traveled with Louisiana public high school students on a two-week educational tour of the Deep South. The trip was sponsored by the Eisenhower Center for American Studies in New Orleans, which had seen my book, WEARY FEET, RESTED SOULS: A GUIDED HISTORY OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT (published by W. W. Norton in January), and decided to use it as a text for the journey.

The program was started in 1992 by historian Douglas Brinkley, who called it the Majic Bus (irregularly spelled to avoid confusion with the song of the same name by The Who). Brinkley, head of the Center, invited me to come on the bus as a teacher. The program featured an impressive line-up of writers and movement veterans, including Julian Bond and Taylor Branch, so I saw it as an opportunity to teach, see some new sights, get back in touch with some people I had first met while researching the book, and see how the book was selling down there. The following are adaptations from a journal I kept during the trip:

New Orleans, April 4 - When I showed up at the Eisenhower Center, the students, a racially mixed group, were just arriving, each accompanied by a teacher from his or her school. They were not just from New Orleans, as I had first thought, but also small towns scattered across the state like Covington, Logansport and Sun. None had ever crossed the Louisiana border before, except on short family visits. Few had been away from home for any extended time. They were quite shy at first, and the rain streaked some of their name tags. I showed one how to operate a push-button coffee dispenser.

At the Center, where books on World War II lined the walls, Doug Brinkley gave his launch speech to the students, while taking two phone calls. Judging from his accomplishments, I already knew he was a formidable multi-tasker (Majic Bus visionary, biographer of several U.S. statesmen, editor of Hunter Thompson's letters, author of countless articles and perpetual radio guest). But I wasn't prepared for the boyish figure who bounded into the room that morning with straight brown hair, already loosened tie, corduroy jacket, and hiking boots. His first speech (which several students dutifully recorded with their camcorders) emphasized the collaborative nature of the enterprise. It reminded me of the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) meetings I had studied from the civil rights era, during which the prevailing attitude was: "Let's try this. If that doesn't work, let's try something else."

Our first stop was New Zion Baptist Church in New Orleans, where the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which Dr. King headed, was founded in 1957. It had taken forty years to recognize the historic value of the church, and a group of dignitaries had arrived to celebrate the unveiling of a new historic marker. The ceremony at New Zion was quite moving. Louise Tilley, an organist who was at the original meeting, played "Amazing Grace" on the organ. A local councilman quoted Aaron Neville (only in New Orleans) on the importance of staying connected to one's roots. Then Rev. Avery Alexander, one of the preachers at the founding meeting of SCLC, made his way slowly to the podium. He gripped it firmly and gave a gravelly speech about being beaten and scarred in New Orleans and prevailing. He described the literacy tests, the grandfather clauses, the trick questions, all designed to keep him and other blacks from voting. He described how little wooden screens had been used to demarcate the "colored" section of New Orleans streetcars in the 1950s, and how he had tossed a few of them out the streetcar windows. "Why this church?" he asked. "This church accepted us, they had a room downstairs, and they let us use the phone without pay." This was the first civil rights veteran the group had heard from on the trip. The students were so attentive you could have heard a pin drop in the hallway.

|

St. Martinville, Louisiana, April 5 - The bus itself was more luxurious than I expected. It had a bathroom, VCF, plush seats, and cup holders. An LED readout overhead continuously flashed the wrong time. Bobby Trufant, the bus driver, was indisputably in charge while we were in motion. He hung a Tasmanian devil from the rear view mirror and wore a uniform that said "Top Gun" on it when we were in the cities, a polo shirt for the countryside.

The first day on the road we visited a small slave museum on River Road, which featured a spiked iron collar crafted by a local metalworker and an exceptional collection of black dolls. I wondered what had ever happened to the black and white dolls Kenneth Clark used for the famous expert opinions formulated in the historic Brown desegregation cases.

Later that day we drove to Lafayette to hear Ernest Gaines read from The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and had dinner at a low-ceilinged place called Josephine's, which served ribs, corn beef hash, potatoes and lemonade. We spent the night at St. John, a white-columned sugar plantation built in 1840 flanked with oak trees and now owned by the Levert family, on couches and floors. The kids played volleyball on the lawn, pounded on the piano, teased each other and fought over the phone. They eventually settled down to write in their journals. I slept in the dining room, and whoever woke up early to make the coffee in an elegant silver urn nearly tripped over me. The next day we toured the plantation with a member of the Levert family and learned about the sugar harvest. We went to a warehouse and watched a front-loader dig into a mountain of raw brown sugar, which was still sticky from its natural syrup.

The Mississippi Delta, April 8 - The Delta has been described as "The Most Southern Place on Earth," and it looked it when we passed through. Rows of fresh plowed furrows were broken only by a few rusty sprinklers to moisten the ground. Fields of goldenrod stretched out on either side of the road and, except for a few tractors and pick-ups kicking up comet tails of dust in the distance, nothing seemed to move. Everywhere we went outside the big cities, people either stared at us as we drove by or waved - or both. We had to watch our clearance at minor bridges because the bus at 12 feet, four inches tall wouldn't always fit under them.

We were warmly greeted in a small church in Greenwood, a Delta city with a museum devoted entirely to cotton. Here a number of local politicians and preachers had gathered to meet the group, and their stories brought chills to my spine even in the Delta heat. One spoke of never letting a car pass him on the highway for fear of being run off the road. Another described how his church had dwindled to 20 members because of civil rights turmoil. One of the politicians whipped a newspaper clipping out of his pocket and read some recent news that was rich in irony and comeuppance. The paper had reported that Byron de la Beckwith, a white man who had received a hero's welcome in Greenwood after his first trial for the murder of NAACP leader Medgar Evers ended in a hung jury but who ultimately was convicted of the crime, would be spending the rest of his days in the Parchman Penitentiary, the notorious Delta prison. Parchman, located not far from us, was where busloads of black convicts had toiled and served hard time, sometimes on false charges, since the early 1900s. The news about Beckwith brought hearty applause, and the room was filled with feelings of mutual respect and warmth. A soft afternoon light poured in through the stained glass windows.

Afterwards we went to Wal-Mart, and I went to a bookstore at the Greenwood mini-mall that still had Books in Print on microfiche. They had never heard of Weary Feet, Rested Souls, but after I showed them a copy, they ordered a few. For dinner: chicken fried steak, black-eyed peas, and mashed potatoes yellow with butter. And, of course, unlimited refills of much-needed iced tea.

The next day we visited civil rights sites in Money (where Emmett Till was abducted) and Ruleville (home of Fannie Lou Hamer). We heard a concert at the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale. The students danced the busstop in the museum and bought t-shirts and postcards.

|

On the way up to Memphis, our luck took a few turns for the worse. A baseball-sized rock from a passing truck hit the bus windshield and left a star-shaped crack on the driver side. [Someone put a yellow post-it next to it that read: "Act of God"].

The first hotel we checked into in Memphis was rundown, so we moved. Our dinner at a Mexican restaurant left some of us with queasy stomachs. To top it off, Bobby the bus driver accidentally caught the bumper of perhaps the only Jaguar in West Memphis while pulling out of the parking lot. (The bus and passengers were unharmed.) During this time friends and family were calling to see if we had been caught in the deadly tornadoes that had been ripping through Alabama and Tennessee, and the news was flooded with reports of the death of country singer Tammy Wynette.

One student's first comment upon arriving in Memphis: "It's so hilly!"

Columbia and Summerton, South Carolina, April 12 - On Easter Sunday, the group temporarily divided for religious services: half went one way to the Catholic service, and the other half went to a Baptist service (I chose the latter). The Baptist church was a predominantly white church with a wealthy congregation, but they welcomed us warmly as the pews filled to capacity. For many of the students, who were used to clapping and worshiping for up to three hours on a regular Sunday, the service was a mixture of the familiar and the strange. Although they knew many of the hymns and prayers, the shiny horn section, white-gloved handbell ringers and sign language interpreter were new. Afterwards we got back on the bus in our Easter clothes and ate turkey, stuffing and pecan pie out of Styrofoam containers.

The countryside turned to tall pines as we headed east into South Carolina. By contrast to our rough landing in Memphis, the capital city Columbia greeted us with wide, clean streets and a mayor who beamed for the cameras and gave us a brass key to the city. The students were delighted to find teddy bears, rubber ducks and cookies in their hotel rooms, and plastic-lettered marquees announced our arrival everywhere we went in town. Our guide was a hyperkinetic businessman named Sonny DuBose, who hailed from a long line of Confederate ancestors but who was now devoted to civil rights history (and to removing the Confederate battle flag from the Capitol flagpole).

He introduced us to the children of the Rev. Joseph Delaine, whose longtime battle for civil rights in Clarendon County laid the groundwork for the first Brown desegregation case, brought by the Briggs family and several others in the 1950s. We visited Scott's Branch High School, the separate and unequal school at the center of that landmark suit, which originally was a small wooden schoolhouse (today it is a modem concrete facility). There we met with several of the children whose parents had signed the original petition to desegregate the public schools, along with their relatives. I looked at their faces, the family resemblance, and listened to Joseph Delaine, Jr. describe the hostile conditions surrounding that lawsuit. He got choked up in front of the cameras as he described the many families who helped his father in those early days and even volunteered to guard his house. Several of the students whose families had signed the Briggs petition were forced to move away in the 1950s and '60s, but many of the children were returning to the area after 40 years of living elsewhere.

At this point, the road rhythm of the group was becoming second nature. Perhaps most attuned to the routine was Brinkley himself, who had after all done this six times before. Nonetheless, he seemed not to mind that he was wearing the same gray t-shirt and jacket he had started out with, writing and editing on a bus loaded with high school juniors, and trying to arrange our constantly changing schedule with a dodgy cell phone. When we stopped at a gas station, he hopped off and came back loaded down with potato chips, Twinkies, and a 32 oz. blue slushy (sp?). This was a man born to road trip. Meanwhile, the students were desperate to break up our usual meal of chicken and collard greens, and they were starting to agitate (with my support) for pizza and perhaps a movie.

Birmingham, Alabama, April 15 - Our first stop in northern Alabama was the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, a headquarters for civil rights marches that was bombed in 1963 (Spike Lee's recent documentary about the victims was called "Four Little Girls"). Once again, members of the congregation came out to greet us, and the students responded with questions and thanks. I did a stand-up interview with a local TV station on the steps.

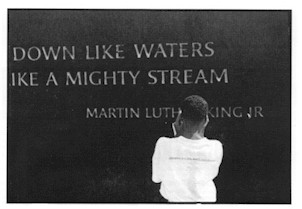

Outside the church, Kelly Ingram Park, where police had loosed fire hoses and German shepherds on protesters, was a combination of stately renovation and a graphic historical exhibition. The center of the park was marked with placid marble fountains, but arranged around the perimeter were cast-iron sculptures of leaping dogs and young protesters behind bars. This public display (along with an extensive museum nearby) is perhaps the most elaborate civil rights memorial yet constructed, and the students wandered through it reflectively, stopping to take pictures here and there. They sat in a circle and read from Dr. King's "Letter from a Birmingham jail."

|

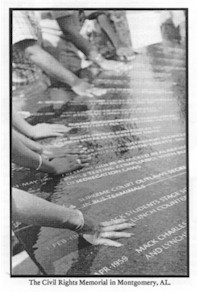

Montgomery, Alabama, April 17 - Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Dr. King's first pulpit and a haven during the famous bus boycott of 1955, stands small and unassuming in the shadow of the state Capitol in Montgomery. We toured the famous church (now a National Historic Landmark), including the mural in the basement depicting various heroes and events of the civil rights period. By now, the students were able to pick out faces and events without any prompting. Up in the sanctuary, we paused for a moment, and Bobby the bus driver led us in singing a few hymns. We followed with a trip to Dr. King's first home in Montgomery, which has a gash on the front porch where a bomb went off in 1956. I described for the group the history of the house, which was occupied not only by the King family but also by King's flamboyant predecessor, the Rev. Vernon Johns. We checked into the Villager Lodge on Interstate 65, and Doug, correctly perceiving that the group was feeling bloated and stiff, suggested a basketball game at the local community center. After working up a sweat in a game of four-on-four, we retired for yet another soul food meal at a local restaurant called Martha's.

Selma, Alabama, April 18 - Our final stop was a special one for me. Selma, Alabama was the first town I visited in 1993 during my initial scouting trip for Weary Feet. Now I was returning to it five years later with the finished book and a group of students who had gotten over their homesickness and had learned more about civil rights in the preceding weeks than I knew until I graduated from college. The road from Selma to Montgomery (called Jefferson Davis Highway) rolled through farmland and a desolate wooded area called Big Swamp. In 1965, civil rights marchers walked the entire 54 miles to show support for voting rights legislation, which was needed to prevent widespread discriminatory practices. Today there is a memorial marker on the highway where a Detroit housewife who came to Selma to assist in the protest was run off the road and killed. We had, entirely by chance, met up with her son at the hotel the night before. He was in the area on a personal journey of his own and had given us a moving tribute to his mother's memory. Several students plucked pink flowers and tossed them before the stone marker that stood by itself in a field just off the road.

Selma itself appeared to be a kind of time capsule. The Edmund Pettus Bridge, where troopers initially turned back the Selma-to-Montgomery march with tear gas, arched over the Alabama River, as it had for five decades. The county courthouse, the churches and the streets evidenced little change. Even the Mayor, a former appliance salesman named Joseph T. Smitherman who had made his name in the 1960s as a young segregationist but had since repented, was still in office.

For our final dinner, we went for an all-you-can-eat buffet at a mall. The students wolfed down spaghetti and ice cream, and a few of them decided to teach me how to stand and move like a rapper. Back at the hotel, we had a final wrap-up session. We went around the room, and the students spoke in turn about what the trip had meant to them. One vowed to take the lessons she had learned back home and become more involved in her community. Another was inspired to write a play about one of the activists we had met. All the students seemed conversant with a talk-show format (many were devoted watchers of Jerry Springer), and many who had said very little during the trip suddenly came out with lengthy observations. As the meeting broke up, they all came by to say a few words to me and to make sure I remembered the handshakes and slang phrases they had taught me on the trip.

~

Originally published: DebeVoice, July 1998.